Tori McEvoy is a PhD student at Queen’s University Belfast, investigating how different levels of socialisation impact puppy behaviour.

Tori is a member of the Breedera Advisory Panel, set up in early 2022 to support our growing dog breeding community.

Composed of experienced advisors with a unique insight into dogs, breeding, welfare, and behaviour, our panel is there to help shape our technology and support our community with help and advice at every stage of a dog’s lifecycle.

About the research

Tori’s research focuses on the benefits of a socialisation protocol for commercially bred dogs and aims to provide recommendations on the timing and content of socialisation programmes.

She is currently finishing up her PhD and has carried out a series of tests to compare the behaviour of puppies exposed to novel stimuli from the age of four to eight weeks with the behaviour of their littermates who have received standard socialisation procedures.

“There’s currently very little legislation regarding the level of socialisation or enrichment a puppy should receive. And this is because there’s been no solid research to back the claim up that socialisation has a positive impact,” Tori explains.

“With my research, I’m hoping to provide some substantial evidence on socialisation.”

What is the impact of socialisation on a dog’s behaviour?

Tori has worked on a commercial breeding establishment (CBE) to conduct her research, carrying out several tests to record the impact of socialisation on behaviour.

“My first experiment looked at socialising individual puppies between six and eight weeks of age. I split each litter as equally as possible between sex so that the results were as reliable as possible. One group received the CBE’s standard socialisation protocol, and the other group was exposed to a series of novel stimuli and experiences” Tori tells us.

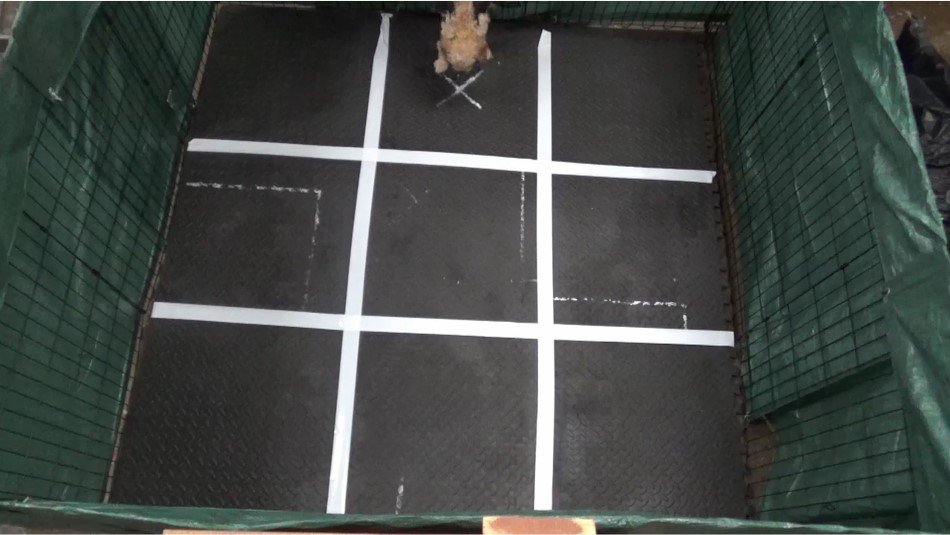

The puppies were placed in a pen marked out by a grid and introduced to several different types of stimuli, including an unfamiliar human, a toy dog impregnated with the scent of a strange dog and various other unusual objects and surfaces.

“We recorded the puppies’ reactions on video – looking at everything from their posture, the time it took them to move away from their starting grid, how much time they spent exploring and how long it took to approach the stimuli.”

The results – although yet to be published in Tori’s thesis – show that the puppies that had received the enhanced socialisation programme showed greater confidence and reduced anxiety.

What are the maximum and minimum levels of socialisation for dogs?

The second experiment explored the maximum and minimum levels of socialisation – the maximum amount a CBE could realistically carry out and the minimum required for the puppies to reach the same level of confidence at eight weeks.

The test introduced adverse stimuli – an electric fan with a human sat next to it.

“The person sat next to the fan would show positive cues towards the fan and encourage the puppy to interact with it,” she continues.

“The idea was that if this type of socialisation was carried out from a young age, when it was time for the puppy to go to their new homes, they would be able to take positive cues from a human when it came to unfamiliar and scary objects and noises.”

Tori is yet to receive the results of this experiment.

Ongoing research at QUB

The third test was based on a previous experiment that compared the behaviour of wolves and dogs.

The puzzle-solving experiment involved placing a plastic tub over a treat on a wooden plank. The puppy must move the plastic tub and collect the treat three times before they move on to the final “impossible task”.

The impossible task is the same, but this time the plastic tub is fixed to the wooden plank – making it impossible for the puppy to ever collect their treat.

“The hypothesis for this one is that the puppies who have received the enhanced socialisation programme would know to look to the human for help – as this is what happened with the dogs in the wolves vs dogs experiment. Meanwhile, the other group of puppies would try and persist and not see the human as a companion who could help.” Tori describes.

“However, although I’ve not received the results yet, so it’s too early to officially say, I have a feeling that my results will be slightly different, and the puppies who have received the standard socialisation protocol will be unconfident and not persist with trying to get the treat.”

Again, the results for the third experiment have not been gathered yet.

Tori is looking forward to her work with Breedera, helping our community with some of their questions about socialising puppies:

“I’m looking forward to speaking with the dog breeding community about the best ways to socialise their puppies and working with breeders to improve the welfare for all different breeds of dog.”

Disclaimer:

*The information provided in this article is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional veterinary advice, diagnosis, or treatment. The content shared here is based on thorough research, personal experiences and the collective knowledge of the dog breeding community.

While we strive to offer accurate and up-to-date information, the field of veterinary medicine is constantly evolving, and individual cases may vary. Always seek the advice of a qualified veterinarian with any questions you may have regarding your dog’s health or well-being.

By Courtney Farrow

Courtney supports Breedera with all our online content. Specialising in heart-led copywriting for purpose-driven brands, she is passionate about Breedera's mission to make responsible breeding practices easy and rewarding and champion more traceability and transparency in the pet industry.